Optimization

In this and the next few modules, we will begin discussing optimization. Specifically, in this module, we will discuss the dangers of premature optimization, as well as looking at a simple optimization around String concatenation.

Trade-offs

Before we continue talking about optimization, let’s take a brief trip into economics.

One of the most popular textbooks in economics is Principles of Economics by Greg Mankiw, an economics Professor at Harvard University. In the book, Mankiw lays out 10 principles of Economics. I am going to cite the first two:

1) People face trade-offs. 2) The cost of something is what you give up to get it

A trade-off is where you have to make a choice between multiple options. For example, if you are buying a car, you may want a car with heated seats. However, you expect to pay more for a car with this feature. When choosing what to eat, we consider not just trade-offs of cost, but of calories, health impacts, etc. When deciding which video game to play in your Steam backlog, you deciding which game you are giving up your time to.

The second principle relates to the idea of an opportunity cost. For example, let’s say I have two choices:

1) Buy a $1600 NVidia Graphics card that has 15% better performance on my favorite games than my current card 2) Put that money in a retirement account, where it could accrue on average say 5% interest over the next, say, 30 years

In 30 years, that $1600 is actually worth $6915.11 (not counting inflation, but even if you assume an average of 3% inflation, it’s still about a 7% increase in buying power, or $2848.93). This by buying a graphics card now, I won’t be able to buy something that costs nearly $7000 dollars later.

Except it’s worse than that. Because it’s not just choosing between a GPU or savings: I also could instead buy years worth toys for my son, or eat out at a fancy restaurant several dozen times, or new video games, or put a downpayment on a car, or…etc. etc. When I make a decision, I give up every other option. That means even putting the money in the bank is still giving up on things, like better graphics for Remnant 2 and dinner at Hamilton’s tonight.

In fact, there is an observable phenomena in humans where, when we are giving more options, we often regret our decision, even if we would have make the same choice with viewer options. This “Paradox of Choice” was described by Barry Schwartz in his 2004 book.

Analysis Paralysis

We want to make software we respond to change, but every implementation detail we make can ultimately come back to bite us, giving us a mountain of refactoring work. A data structure that works now may not work later. A database and server architecture that works when we have a few thousand users completely falls about when we have millions of users.

“The first key to writing is… to write, not to think!”

Finding Forester(2000) - Sony Pictures

However, we cannot allow ourselves to fall into Analysis Paralysis, a condition where we are so caught up worrying about the “best” way to do something, that we end up not making any progress at all. I would typically rather release a working, improvable, but potentially imperfect product efficiently than wait until my product is perfect. The simple reason for this is what we’ve already talked about with design: Change is the norm, not the exception. Perfect software today can be useless in a year.

Irrelevant Optimization

I’ve taught introductory programming classes in Python and Java. Early on I show students a for-loop and a while-loop, and how we can write two loops that are functionally equivalent. Something like, when printing an array:

public class LoopExamples {

public static void printUsingForLoop(int[] myArray) {

for (int i = 0; i < myArray.length; i++) {

System.out.println(myArray[i]);

}

}

public static void printUsingWhileLoop(int[] myArray) {

int i = 0;

while (i < myArray.length) {

System.out.println(myArray[i]);

i++;

}

}

}

When I show this, almost every single semester I have taught intro, I have had a student ask “Which is faster?” And I always tell them the same thing. “I don’t care.” The reason for this is that this is an introductory programming class; I want to focus on getting students to write working code first.

Eventually, the question will come up again. At this point, I’ll say why you should use either loop. Typically, this is something like:

-

Whenever you are iterating over something, like a set of numbers or a collection, you should always use a

forloop of some kind. Use an enhanced for loop, likefor (String word : dictionary )when you only care about the values, but use a traditional “counter” for loop if you need to keep track of indices or you care about order. -

A

whileloop should only be used when you cannot easily calculate the number of loops you will need at runtime. For example, when prompting a user for input in a command-line application, I will often check their input validity and, if it’s invalid, prompt again. I will keep repeating this until the user enters valid input. There’s no variable or piece of data that can tell me how many loops that will take, I’m simply looping while I don’t have valid input.

Notice that I never say anything about efficiency. That’s because the most common problem I see with students is they tend to overuse while loops, and in doing so are more likely to create infinite loops (it’s easy, for example, to forget to write the incremental step when use a while-loop; I see even experienced programs make that mistake). I’m far more worried about preventing bugs than about any “optimization gains.”

For the note, typically in Java, the two are the same (because they often compile to the same or nearly the same virtual machine code). In some cases,for loops are very slightly faster. But even if they weren’t, and they were somehow slightly slower, I would still recommend using for loops over while loops for iteration. That’s because I have created far more bugs with incorrect while conditions than incorrect for loops. If I was forced to weigh a nanoscopic, if not outright imaginary, performance increase against time spent debugging silly mistakes, I would save myself the debugging every time until I absolutely cannot afford to.

With apologies to Sonic the Hedgehog, you do not “gotta go fast”. Do not aspire to always write perfectly optimized code. Not only is this a fool’s errand doomed to failure that will drastically slow down if not actually halt your progress, but it will also make your code harder to adapt and change, as we’ll see in the next module

Code Trade-offs

Efficiency is one of several goals we care about in software. But it is not the only goal. We care about functional correctness, robustness of features, usability, portability, etc. And all of those are just external considerations. We also care about code maintainability, analyzability, changeability and testability. A clear example of this is abstraction! We absolutely value abstractions because they greatly improve the modifiability, flexibility, and replaceability of our code. Using a HashMap, but you need sorting? Use a TreeMap! Replacing the HashMap with a TreeMap can be as simple as changing one line of code if you are using abstractions. Is the TreeMap too slow? Go back to the HashMap!

However, by their very implementation, abstractions decrease performance. But that’s okay! Java is full of abstractions, but it’s also an easy language to write in. In the next unit, we will look at a concrete example of a trade-off between simplicity and performance. You don’t have to worry about handling your memory, Java abstracts away that need with garbage-collection. Garbage collection is a feature that automatically frees unreferenced memory.

Several modern languages, especially C, C++, Rust do not have garbage collection, and rely on the programmer to manage their own memory (similar to constructors to create objects, you will have destructors to effectively destroy objects which must be called manually before dereferencing an object). This makes these languages harder to program in, since you necessarily have to keep memory management in mind. The benefit? These three languages are typically considered the three fastest languages.

If all we cared about was efficiency, ease of programming be damned, we would all only write code in C, or even worse in Assembly (which is only one level above “byte code”). Efficiency is just one other goal.

To be clear, there is absolutely a time to worry about performance. But most bad performance problems I see students make are simply using incorrect algorithms (like selection sort instead of merge sort) or incorrect data structures (using a List when a Set or Map would be better). Efficiency absolutely matters - if you have an efficiency problem, you should fix it. And the fixes may reduce other qualities like readability, simplicity, etc. But you should only take those steps when needed, not by default!

Don’t listen to me

This is not an original opinion on my part. And you may be asking why should you take me seriously when I say “Don’t worry about performance” After all, I’m not an algorithms expert. Instead, listen to Donald Knuth, who is often called the “father” of algorithmic analysis. Surely he’s going to care more about efficiency than anything else, right?

“Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of noncritical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil…” Donald Knuth, 1974, Structured Programming with Go To Statements, Computing Surveys Vol. 6, No. 4

There is an important finish to that quote, as I will in a second, but I want to break a few things down first. The key takeaway, however, is that the “father” of algorithm analysis is telling you to not worry about performance to the exclusion of all else.

Critical vs. Noncritical

When Donald Knuth talks about “noncritical” parts of programs, he is talking about sections of the code that simply cannot affect performance that much. A humorous, though dark, way to imagine this is someone throwing a drink over the side of a sinking ship to reduce how much water it’s taking on due to a massive hole in the side of the ship. Yes, if your ship has a massive hole filling the hull with water, you should fix that. But throwing your Old Fashioned overboard is just a waste of good bourbon.

Far too often, I see students and programmers arguing over absolutely irrelevant nonsense, berating colleagues and project teammates over using i++ instead of ++i, and which is more efficient.

The following video by code aesthetic summarizes this argument, and how absolutely useless the argument is (You can stop at the 8:00 minute mark, but I recommend the entire video, and all of Code Aesthetic’s Youtube videos) :

Only, now, I need to finish the Donald Knuth quote:

“…We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil, Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%”

In general, a critical section of a piece of code, be it in a single module, class, subroutine, or overall piece of software, is the section of code that costs the most time overall.

Critical section

For example, consider the following intentionally bad and inefficient code. In this program, a user can search for any String in the [Adventures of Sherlock Holmes], and this will print a String with every line where it is found.

Be warned, this code has an intentionally bad use of Strings, as well as some bad style. This is because this is code adapted from something I’ve seen from a student before, and I preserved some of the decisions.

public class SherlockSearch {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

BufferedReader bufferedReader = new BufferedReader(new FileReader("sherlock_holmes.txt"));

Scanner scanner = new Scanner(System.in);

System.out.print("Enter a word or phrase you wish to search for: " );

String target = scanner.nextLine();

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

String message = "We are now searching for ";

message += target;

message += "\n. Please stand by...";

System.out.println(message);

int currentLineNumber = 0;

int count = 0;

String results = "";

for(String line = bufferedReader.readLine(); line != null; line = bufferedReader.readLine()) {

if (line.toLowerCase().contains(target.toLowerCase())) {

results += currentLineNumber + ", ";

count++;

}

currentLineNumber++;

}

String endingMessage = "Thank you for waiting. Your query for: ";

endingMessage += target;

endingMessage += " returned ";

endingMessage += count;

endingMessage += " results:\n";

endingMessage += "\t";

endingMessage += results;

endingMessage += "\n";

System.out.println(endingMessage);

long endingTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("Your search took " + (endingTime - startTime) + " milliseconds");

}

}

I added two lines to benchmark my code (that is, judge its efficiency). If I pick a word I’m confident Sir Arthur Conan Doyle never used, like “Internet Memes”, this is how my code runs:

Enter a word or phrase you wish to search for: internet memes

We are now searching for internet memes

Please stand by while we search...

Thank you for waiting. Your query for: Internet memes returned 0 results:

Your search took 30 milliseconds

If I run with “internet memes” several times, I get runtimes of anywhere from 25-30 milliseconds. It’s a pretty wide range, and a lot of the noise will have to do with other processes my computer is running. But keep that range in mind.

If I search for a shorter String that doesn’t exist (“qzj”) since the second string is shorter, you might think it would be faster, but it actually is a little slower, since you have to check more letters (contains is optimized to stop search if there are fewer characters left in the string than you are searching for.) I typically go 27-35 milliseconds, so not bad.

But now let’s try a word I know Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote: “the”.

Enter a word or phrase you wish to search for: The

We are now searching for The

Please stand by while we search...

Thank you for waiting. Your query for: The returned 5317 results:

4, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 63, 64, ...

Your search took 44 milliseconds

With 5317 results for “the”, our search took 44 miliseconds. Over several runs, I generally saw times 40-45ms on my computer.

Why is this slower?

Well, maybe, you think, it’s because it’s running more lines of code. After all, we have this if-statement inside the for loop. Indeed, the problem is actually here, but understanding the problem requires a deeper understanding of how Java Strings work.

if (line.toLowerCase().contains(target.toLowerCase())) {

results += currentLineNumber + ", ";

count++;

}

One obvious problem you may notice is that every single time through the loop, we are calling target.toLowerCase(). But we really only need to call it once. After all, “The”.toLowerCase() is going to give the same result no matter how many times you call it.

So we make the following adjustments. When getting our target from the Scanner:

System.out.print("Enter a word or phrase you wish to search for: " );

String target = scanner.nextLine().toLowerCase();

…and then in our if-statement…

if (line.toLowerCase().contains(target)) {

results += currentLineNumber + ", ";

count++;

}

That’s gotta be a lot faster, right? After all, if there are 10000 of thousands of lines, that’s 9999 fewer calls to toLowerCase().

Well…it made a small difference, but not as small as you think. With “The”, I was seeing 39-41 milliseconds (improved over 40-45ms). However, with “Internet Memes”, I really didn’t see any improvement, it was still 25-30ms consistently. That if-statement didn’t make much a difference it seems. So why is “The” still taking nearly half again as long as “Internet Memes”

String Concatenation

The culprit is actually this line:

results += currentLineNumber + ", ";

Specifically, the problem is that line being in a loop. When you concatenate 2 Strings of length n in Java, the runtime is O(n). That is, if the two String are longer, the concatenation takes longer. This is because Java concatenates the String by creating a new memory allocation to store the combined String (n + n length), and then copies the values over one letter at a time.

The problem with this? This means every single time we concatenate a String, we are performing an O(n) operation. Except it’s worse than that, because our String gets longer and longer, this means our n gets bigger and bigger. As a result, concatenating k number Strings of length n in this fashion ends up being an O(k^2 * n), or quadratic relative to number of String objects. This means each concatenation is taking up significantly more time than the last.

StringBuffer

Instead, we should use a StringBuffer, which works like an ArrayList, allocation more space than needed in sequential memory, and if it ever needs more space, it doubles in since. This means we are getting amortized constant time for each new character, meaning the whole process is **O(k*n)**, or O(len) where len is the length of the final String. This is linear time. If I make that change:

StringBuffer resultsBuffer = new StringBuffer();

for(String line = bufferedReader.readLine(); line != null; line = bufferedReader.readLine()) {

if (line.toLowerCase().contains(target)) {

resultsBuffer.append(currentLineNumber)

.append(", ");

count++;

}

currentLineNumber++;

}

...

endingMessage += "\t";

endingMessage += resultsBuffer;

endingMessage += "\n";

System.out.println(endingMessage);

If you are unfamiliar with StringBuffers, all you need to know is that the append function adds the String representation of its argument to the StringBuffer’s contents, and that the toString method (called implicity on the 3rd to last line) returns the contents of the Buffer as a String.

With this change, I’m finding I tend to finish the search in 27-32ms, a substantial improvement over 39-41ms (about 25% faster). Because I do need extra code whenever I find a match, I will always get somewhat slower results when I have a larger number of matches, but that’s okay. This is still significant better.

Noncritical improvements

“Well wait a minute”, you might say, if String concatenation is bad, let’s replace all of it with a buffer. That will improve, right?

public class SherlockSearch {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

BufferedReader bufferedReader = new BufferedReader(new FileReader("sherlock_holmes.txt"));

Scanner scanner = new Scanner(System.in);

System.out.print("Enter a word or phrase you wish to search for: " );

String target = scanner.nextLine().toLowerCase();

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

StringBuffer message = new StringBuffer();

message.append("We are now searching for ")

.append(target)

.append("\nPlease stand by while we search...");

System.out.println(message);

int currentLineNumber = 0;

int count = 0;

StringBuffer resultsBuffer = new StringBuffer();

for(String line = bufferedReader.readLine(); line != null; line = bufferedReader.readLine()) {

if (line.toLowerCase().contains(target)) {

resultsBuffer.append(currentLineNumber)

.append(", ");

count++;

}

currentLineNumber++;

}

StringBuffer endingMessage = new StringBuffer();

endingMessage.append("Thank you for waiting. Your query for: ")

.append(target)

.append(" returned ")

.append(count)

.append(" results:\n")

.append("\t")

.append(resultsBuffer)

.append("\n");

System.out.println(endingMessage);

long endingTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("Your search took " + (endingTime - startTime) + " milliseconds");

}

}

Well…not really for a couple reason. The first reason is that we are only concatenating at worst 8 String using our StringBuffer. For us to see a noticeable improvement, we need to have a much larger number of String objects. The second reason is that initializing a StringBuffer and using the append the toString functions comes with an overhead cost of allocating the memory of the StringBuffer as well as loading in the compiled instructions of the StringBuffer. The third reason is actually that Java will optimize sequential String concatenations to optimize concatenation, and our message and endingMessage concatenations are all sequential. The concatenation inside of the for loop, however, cannot be sequential, as we do not know if we need a longer String until we do, so Java cannot optimize it.

But the biggest reason is that message and endingMessage are constructed in a non-critical section. Each section of code is only executed one time. The vast majority of the time this code spends executing is inside the for loop. The body inside loop is executed 12196 times (the number of lines in the file). Additionally, for when we searched “The”, the body if the if statement executed 5317 times. This means any optimization to our code inside the if-statement will have 5 orders of magnitude the impact of the same optimization outside of the for-loop.

Finding the Critical Section

A general rule of thumb: the more a piece of code is executed, the more critical it is. If your code contains several loops (including loops contained within functions called by other loops), the inner most loops are going to be points of internet.

Another useful tool is a profiler. In IntelliJ Ultimate, you can run a Profiler that will highlight which lines of code took the longest. In general, it’s good to disable any user input when running a profiler, since any time the program is “waiting” on user input will count as time spent on the line of code where the input is collected. So if I simply change the line where I use String target = scanner.nextLine().toLowerCase() to String target = "the" for the time being, I can execute my test. (Of course a better solution would be to decompose my code into separate testable modules, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s skip that).

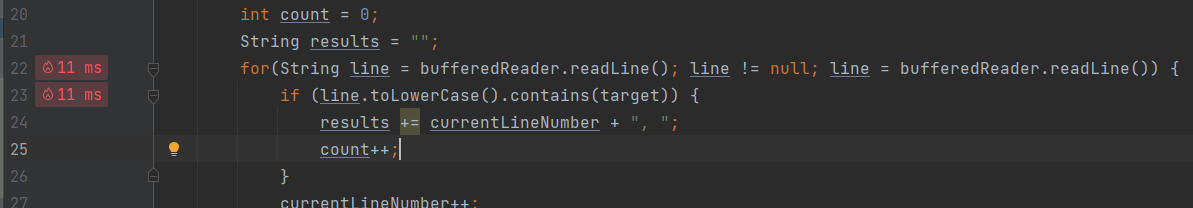

If I ran my profiler before I made the StringBuffer change, I could see the problem lines:

Note that the profiler also tells me that the readLine calls are also taking up a significant portion of the programs runtime, but there’s nothing I can do about that. I/O with files is typically going to be relative slow simply because loading resources from hard drive storage is even slower than memory, so there’s not much I can do about that. However, profilers can help you find low hanging fruit.

The Lesson

While knowing when and how to use StringBuffers is valuable, the biggest thing I want you to takeaway from this unit is that trying to overthink how to maximally optimize every line of code is often wasted effort. Instead, focus on critical sections and look for obvious optimizations. Often, simply using appropriate data structures and algorithms can make substantially larger improvements than many “micro optimizations” you will read about in Stack-Overflow arguments.