Packages

In this unit, we’ll discuss Java packages, how to use them, and how to create them.

This Module’s Source Code Example

Contents

- What are Packages

- Importing packages

- Creating packages

- Why bother?

- Naming packages

- Reusable code

- Adding Jars as Libraries

What are Packages

In Java, code is typically organized into packages of related or interacting classes. Consider for example the package

java.util. This package contains, among other things, the Java Collections framework.

This includes classes like ArrayList, HashMap, TreeSet, etc. These are classes that we use whenever we want to use

a collection. However, by default, these classes are not accessible in Java the same way that the classes String or

Integer are. Rather, these classes have to be imported.

Importing packages

Whenever you want to use code from an external package (that is, code someone else wrote and has made available to you via a package), you simply import it.

import java.util.*;

import java.io.*;

These two import statements pull from built-in libraries in the Java runtime environment. java.util includes

many common utility classes, like collections, Date objects, Currencies, etc. java.io includes

many classes needed for File IO, like FileReader, BufferedReader, and PrintWriter. We don’t always need these classes,

but when we do, we can access them by importing the class.

A note on import statements

Disclaimer: the following advice can be seen as controversial, and some people suggest you should never manually manage import statements. My general view is that someone reading your code should be able to, at a quick glance, see what packages you use. I’ll just note some people disagree with the following advice.

Often, I will see programmers write things like:

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.HashMap;

...

This typically happens because…well…that’s what IDEs do by default. However, it’s not “more efficient” to do imports

this way, all this does is take up screenspace. As a general rule, it’s fine to just use import java.util.* whenever

you’re using anything in the java.util library.

The only reason you would import individual classes is if you are worried about a name conflict. For example, both java.util and java.awt have a List class. So if you imported both libraries:

import java.util.*;

import java.awt.*;

And want to specifically use List, you would have a name conflict issue. Java wouldn’t know which List you meant,

util or awt. The solution is to simply add which List you want to use.

import java.util.*;

import java.awt.*;

import java.util.List;

This will tell Java “when I say List, I mean java.util.List”. This is the only time you need to tell Java to import a specific class. Otherwise, it is sufficient to import an entire package.

Creating packages

When you create a package, you are effectively creating a sub-folder in your source code directory that acts as a package. When classes are added to a package, most IDEs will automatically add their package declaration at the top.

For instance, if you look at my DateGetter class for today’s source code example, at the top of the file, you’ll see:

package edu.virginia.cs.dategetter;

This means that this class is in the package edu.virginia.cs.dategetter.

Why bother?

So now you are likely asking the obvious question. Why would I care whether my code is in a package or not? Well, for the types of assignments you’ve done so far, you probably don’t care, because each assignment was something you built once and threw away, never to look at again.

Sharing code

But what if you wanted to share your code? Remember, as we talked about in the last unit, it’s nice if we can bundle up all our files into a single .jar file and share that, rather than sharing source code or individual class files.

However, if I want to share my code, I don’t want to use the default namespace. The default namespace is what’s used when you create classes that aren’t in any package. The problem with using the default namespace is that any class you create cannot overlap with any classes you use, or you’ll have a name conflict.

The solution is to put your reusable code in a package. Then, if the user wants to use your classes in a particular .jar file, they can simply import the relevant package(s) they need only for that file. You aren’t polluting the global namespace.

Design Considerations

Something that we will eventually talk about is modularity. We want each part of our program to have a singular clear purpose. If we had a portion of a large program that could be detached and reused, separate from the rest of the program, it could benefit us to put that separable portion into its own package. Then, if we want to re-use that sub-program, we can simply import that package in our other programs!

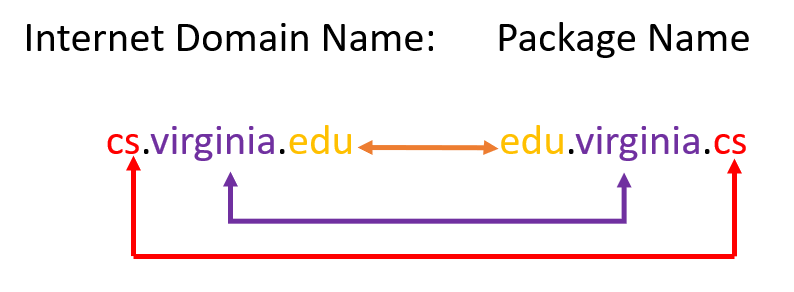

Naming packages

A general rule when it comes to naming packages is “reverse Internet domain name.” For example, the internet domain that

would most easily be associated with this class is cs.virginia.edu. So in this class, most of

the packages I create are going to have names that start with: edu.virginia.cs.

Now, because I’m making dozens and dozens of projects, for example in this class, I don’t want everything in the same

package, or I have to start worrying about namespace concerns. So, my general pattern is edu.virginia.cs.[project-name]

If I release a jar that contains code I wrote for class, like this dategetter.jar here, people can use this code by downloading the .jar file, adding it to the libraries in their project, and then simply importing my code when they want to use it. For example:

import edu.virginia.cs.dategetter.*;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

DateGetter dg = new DateGetter();

Date currentDate = dg.getCurrentDate();

System.out.println("Today's date is " + dg.getMonthDayYearDate(currentDate));

}

}

This is beneficial as well, because the class name Date is likely to be very very common, and so I want to

ensure that people are able to still use my code without worrying about name conflicts. If they have to pick

between one of two Dates, they can simply import the specific version of Date they want in each class (or refer

to the class with its package name in the full code to use both).

Reusable code

This is the crux of modern software engineering: We don’t want to reinvent the wheel! Why write our own code to parse JSON code when we can use org.json, which has not only implemented it already, but is well-implemented, heavily tested, and well documented, with tons of other users? Why write our own Stacks and Queues when we can use java.util’s Vector class, which implements both a Stack and Queue interface?

Even better, we can do all of this without copying and pasting a bunch of individual source code files around, because when we compile our classes into a .jar, the package names are preserved.

Adding Jars as Libraries

This is something that we will talk about a lot more with gradle, which makes this process very painless and easy.

However, most IDEs (and certainly IntelliJ) make this process reasonably painless once you know what you are looking for.

Generally, in IntelliJ, the simplest (though not easiest) way to add a library is get the library as a .jar file, copy and paste it into the project folder, and then right-click the .jar file and find “Add as Library…“. However, when we discuss Gradle, we will discuss a much easier way to add external libraries that won’t require any manual downloading.