“… the greatest limitation in writing software is our ability to understand the system we are creating.”

- John Ousterhout, A Philosophy of Software Design, Chapter 1

What is Design

Design, in software, refers to the organization of our code, including classes, functions, and the relationships between them. No matter how we construct our software, our software has a design. The question is: is that design any good?

Before diving into design

Design is, in my opinion, far and away the hardest topic we grapple with in this class. The reasons for this are myriad, and include:

- You often don’t know a design has a flaw until faced with a change that reveals that flaw.

- There is no such thing as a perfect design - no design can easily handle all changes it could ever face.

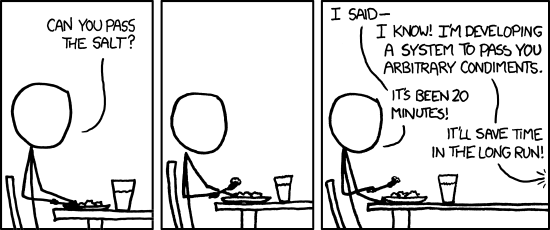

- In the same way software can be under-designed, it can be over-designed. While underdesigned software will not be receptive to change, and will be extremely difficult to maintain, over-designed software can become difficult to navigate and understand, as over-design often results in too much fragmentation of key ideas.

- The needs of a design are subjective to a particular problem. Sometimes we need significantly more adaptability, sometimes we need less.

- Ultimately, measuring design quality is itself subjective. Different people with different experiences will have different levels of difficulty understanding and modifying the same level of design.

As such, I guarantee that there will be things in the Design unit as a whole that people disagree with. There will be some suggestions that work well in some situations and badly in others. However, we will focus on the overarching design principles, common understandings of how to best maximize those principles, but also not lose sight of the real purpose of software: “To meet the needs of the customer.” Design is a means to an end, not the goal itself.

What makes a good design?

Of course, the question of what is a “good” design doesn’t have any obvious answer. In physical systems, such as bridges, home appliances, cars, etc., we often think about design related to “how long the system works before degrading.” That is, the Golden Gate Bridge must be well-designed, because it has been open for over 85 years now and is still meeting its goal. A car is well-designed if it last 200k miles and 10+ years.

And sure, these things have maintenance costs; the Golden Gate Bridge has had its deck replaced because of salt in the fog corroding the rebar, and I have had to change the oil and do significant transmission repair on my personal car. But ultimately, the goal of this maintenance is to ensure that the product operates the same as it did before.

Software changes

The fundamental difference is that software is, for all intents and purposes, completely malleable in a way that these physical items cannot be. For instance, the main cables of the Golden Gate Bridge cannot be replaced. The cables are holding up the bridge, and if they are removed, the bridge would collapse. Additionally, while I can replace parts on my car to maintain it, I cannot dramatically change the car. My car is an economy hatchback that cannot easily fit passengers in the back seat. When I have older kids not in car seats, I will eventually have to replace it if I want to be able to fit them in the back seat as they age. I have no expectation of modifying the car to add more leg-room in the back.

On the other hand, software is expected to evolve to meet new needs! However, just because it’s easier to retrofit software than my little Ford Fiesta, that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Anyone who has tried to fix one bug in their code, only to introduce three more, can attest to the difficulty of changing software.

Software Entropy

The difficulty is that as we add features to software, it becomes more complicated. And the more complicated our software is, the harder it is to understand, and therefore the harder it is to maintain. This means changes take more effort measured in developers-hours, which is a stand-in for “cost,” as developer time is the most valuable, and often most expensive, cost of software development. The practical effect of this is that as software ages, it requires more time to implement fewer improvements, as software development grinds down. Entropy in any form is almost certainly unavoidable. However, a good design can dramatically slow the growth of entropy and reduce the overall effort required to make a software change.

“The measure of design quality is simply the measure of the effort required to meet the needs of the customer. If that effort is low, and stays low throughout the lifetime of the system, the design is good. If that effort grows with each new release, the design is bad. It’s as simple as that”

- Robert Martin - Clean Architecture Chapter 1

Planning for change

Thus, the key to design is to expect and prepare for change. That can be anticipating what could change (even if we are not certain exactly what will change - and we never will be) and planning designs to allow that change. However, ultimately, some new change can and will catch us off guard. At that point, we want to compartmentalize individual aspects of our system as best as we can so that change is unlikely to propogate.

A note on over-design

All of the above shouldn’t encourage “over-design.”

Whenever designing a system, we should consider the long-term lifecycle of the software we intend, and how critical the software is (that is, what are the consequences of it failing). For long-term safety critical systems, such as Air Traffic Control systems, we may accept doing some over-design if it ensures reliability and safety.

On the other hand, if our software is single purpose, and expected to have a short lifespan, we may find that we are okay with the software being more brittle (that is, hard to change or repurpose).

For example, in the Fall of 2022, CS 3140 used Collab, an open-sourced LMS (leaning management system). I gave quizzes on the web-application, which students can take multiple times and get their highest score. If a student gets 80% or more of the answers on a quiz correct (taking their best score), I want to give them full credit. Collab lets me download an Excel file (specifically, .xls, or Microsoft Office 2003 and earlier) that contains all the students’ quiz submissions. So in my program, I want to:

- Open and parse through a .xls file - the Student ID is in column 4, while their score is in column 8

- Find each student’s maximum score submission

- If the student’s score is 8 out of 10 or above, give the student 100%

- Otherwise, give the students their score as is, so 6 correct answers is 60%

- Save all student scores to a .csv file format that can be uploaded to Collab’s Gradebook, which requires the student ID in column 1

A lot of the features here could change:

- The export format from my LMS could change to .csv, .xlsx. .json, etc.

- The column numbers with the student ID and total score could change

- The identifier could change from the student ID to the student number

- I might change the score threshold from 80% to 90%

- Quizzes may have different numbers of questions in the future

- The upload format to my online Gradebook may change, or I may have to upload grades to a different system (such as Canvas, which we switched to the follow semester)

There are dozens of additional changes that could occur that might affect my script. Did I account for them in my design and plan my design to be receptive to that change? No. Why not?

- The entire program is relatively small, only about 100 lines of code total.

- There are only two people who will use this script for the foreseeable future, and both of us are CS professors. As such, I don’t need to worry about making the software “user-friendly” as I would with software I would plan to release publicly.

- The course will no longer use Collab starting Fall 2023, and will instead use Canvas, a different LMS system that the University of Virginia is switching to. Thus, any software I write for Collab will be useless in a year anyway.

In summary, don’t overdesign for changes that might occur until you know those changes are needed. And always consider the possibility that it may be easier, especially with smaller single purpose programs, to simply re-implement.

Agile Design

Design should take into account your expectations for the life of the software. The longer you expect software to last, as well as the more you expect software to evolve to changing user needs, the more you should consider your design decisions.

In practice, most commercial software, even “microservice” web application software, will still need to evolve and change, and have a long lifespan. But an advantage of agile development, where software is repeatedly improved and modified iteratively, is that we can refactor design elements later on as our needs change. That is, no design decision is truly permanent (although some changes can become infeasible to change). This is why we spent so much of our last unit (Refactoring) focusing on writing code that can be understood, changed, and resistant to change. Because ultimately, every design could eventually fail, and we will always have to change at least something we didn’t anticipate.

As such, a common practice in agile development is a modular design that can be evolved and changed over the life-cycle of the software. This is what we will focus on in this class.