Software Complexity

“We demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!”

–Hitchhiker’s Guide to that Galaxy, Douglas Adams

In this module, we will discuss why writing software is so complicated, and what kind of difficulties we will face as programmers trying to meet the needs of our customers.

Contents

Hidden Complexity

Software failures are easy to occur because software is essentially complex.

Let’s look at Google.com:

Seems simple enough! What’s that, like 20-30 lines of code, right? In most browsers, you can right-click on the page and go to View Source. Here’s what you’ll see:

The Horror!

This page has a massive source code base! Each of these lines you are seeing are large functions, with hundreds of lines, variables, etc. And yet, you’ve almost certainly never dealt with any of this code before. That’s because, as a user, you are on the customer side. If you need to ever even see the source code of software you are using at a consumer level, chances are something has gone very wrong.

Why do we write software?

We write software to solve problems. That problem might be “when is my next meeting,” or “I need to book a flight,” or “who won the football game last night,” or even “I’m bored, let me play a game to stave off this boredom.” Many of the problems we solve had solutions before software, but software can make it easier, more efficient, more available, and more accurate.

And yet, even simple sounding problems can have tons of hidden complexities.

George Washington’s Birthday

Let’s write a program to tell us how many days old George Washington is. How hard can this be?

Well, since we’re on Google anyways, let’s ask it what Washington’s birthday is.

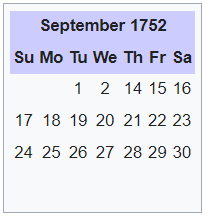

Wait, what!?!? So which is it? February 22, 1732, or February 11, 1731? To add to the confusion, the Washington family Bible notes that George Washington was born “11th Day of February, 1731/2”. And even if we could pick a date, as we go back through the calendar of England, which was the calendar used in the colonies, we see this:

What the heck was going on in September? Well, as some of you may have guessed, like every other confusing bit of European history, this has to do with religious schisms. In 1582, the then Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian Calendar, which is used in the United States and most of the world today. However, England and many other Protestant European countries continued to use the Julian calendar that was already in place for centuries. Because these calendars handle leap years differently (specifically, years like 1700, 1800, and 1900 are Leap Years in the Julian calendar, but are not Leap Years in the Gregorian calendar), the calendars wouldn’t agree on what day it was. February 11th on the Julian Calendar is the same day as February 22 on the Gregorian calendar, because the two calendars had drifted 11 days apart!

What is the start of the year?

Another relevant detail is that the “first day of the year” in England used to be considered “the first day of Spring.” And as such, March 25 was “New Year’s Day” in England during and after the Middle Ages. So February 11, 1731 (Julian) is the same day as February 22, 1732 (Gregorian). However, England (and by extension the Colonies) did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1752, 20 years after Washington was born. But all of this means your program could have produced incorrect output if you didn’t know and account for this history ahead of time!

Time presents all sorts of challenges, as shown in the Computerphile video below (it’s a great channel, by the by).

The Software Crisis

Many are familiar with Moore’s Law, which describes the increase in complexity of computer hardware over time. And while there is certainly a ceiling in Moore’s Law (transistors can only be so small before you run up against fundamental barriers like the size of molecules) , what cannot be disputed is the absolute meteoric growth in computing power in the last nearly 80 years since the construction of ENIAC. A common saying is that your phone has more processing power than the Apollo program, though don’t confuse that with being more capable for the task.

However, while hardware grew exponentially faster and faster for decades, the software that used the hardware…didn’t. By the 1960s, software development skills were already seen as behind hardware at the industrial level. While the machines got more and more powerful year after year, programming skills, techniques, and abilities weren’t improving at the same rate, and in fact weren’t improving much at all. The bottleneck for major computing undertakings became more about the programmers than about the computing resources. This became known as the “software crisis”.

No Silver Bullet

Unfortunately, the software crisis remains an unsolved problem. In 1986, Fred Brooks wrote, in his famous essay “No Silver Bullet”:

“There is still no single development, in either technology or management technique, which by itself promises even one order-of-magnitude improvement with a decade in productivity, in reliability, in simplicity.”

What has happened since? Have we seen any improvement? Yes! Software development methodologies have improved efficiency. Libraries and APIs have improved code reusability. Things have gotten better. But, yet, Fred Brooks is right. None of those things were an order of magnitude in a two year period. We still have significant difficulty writing software effectively. We still haven’t seen a velocity of improvement even close to hardware resources.

Take a moment and read the first 4 pages or so of No Silver Bullet. You will, however, be expected to read the whole article for class. Proceed after you have read the first 4 pages and to the top of page 5 (stop at “Past Breakthroughs Solved Accidental Difficulties”).

Essential and Accidental Difficulties

One of the key takeaways from No Silver Bullet is that software difficulty is made up of difficulties that are essential and accidental.

Essential difficulties are that are intrinsic to developing software. These difficulties cannot be separated from the software development process.

Accidental difficulties emerge because of circumstance. For example, in the 1960s, most programs were written on pencil and paper, and transcribed into punch cards. This process was slow, and great care had to be taken to ensure cards were punched correctly and ordered correctly. These difficulties can be address by improved technology (like keyboards, IDEs, GUIs, etc.).

Imagine if you had a stripped screw that you were trying to unscrew. The fact that it’s difficult to unscrew isn’t essential, as if the screw weren’t stripped, it would be very easy. However, if I asked you to “build a bookshelf”, then that is essentially more complicated than unscrewing a screw, even if you removed all accidental complexity and shop at IKEA for “Billy” the bookcase.

The crux of Brooks’s argument is that there are essential difficulties that will never completely go away. Developing software will always be hard, even as our technological and methodological improvements gives us more power to thwart the accidental complexities. While technology can help us be better and more efficient at writing code, it doesn’t help us solve problems related to specification, design, etc.

And this idea has held up. “No Silver Bullet” is considered among the most, if you’ll excuse the word, essential readings for software engineers. In February 2021, IEEE’s Computer Magazine published “There Is Still No Silver Bullet”, a reflection nearly 35 years after No Silver Bullet was published. To quote the author, David Alan Grier, “Yet, almost 35 years after he wrote this contribution to knowledge, Brooks’s observation remains true. Software engineering is a complex and demanding field that poses a host of problems to the practitioner, and there is no single solution, that is, no silver bullet, that will provide a simple way to reduce the work required to create a software product.”

Programming is hard because the problems we are solving are themselves hard and full of hidden complexity. And if you still aren’t convinced, I have only one question:

How many seconds old is George Washington (be sure to include time zones, leap seconds and Daylight Savings where appropriate. Also, be aware that any consideration for Daylight Savings in your solution has to work differently for people in Arizona, and might have to change in 2023. No wait, just kidding, the house never took up the bill, so we still have Daylight Savings. Unless the House takes up the bill and votes in favor of it).

“Let’s think the unthinkable, let’s do the undoable. Let us prepare to grapple with the ineffable itself, and see if we may not eff it after all.”

– Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, Douglas Adams